Give me that old-time religion,

Give me that old-time religion,

Give me that old-time religion,

Give me that old-time religion,

It’s good enough for me.

The merits of old-time religion seldom are displayed to better and tastier effect than the delicious ales brewed on the premises of six Trappist monasteries in Belgium, which beer lovers typically identify by the names of the nectars they produce: Achel, Chimay, Orval, Rochefort, Westmalle and Westvleteren in Belgium, and Koningshoeven in the Netherlands.

It bears noting that earlier in 2012, Engelszell Abbey in Austria was approved as the eighth Trappist brewing monastery, but of course we’ll have no idea what to make of its beers until Rate Beer and Beer Advocate tell us exactly what to think.

Pious Americans of the Mitt Romney ilk periodically are shocked that a religious order would dare to produce alcoholic beverages. They shouldn’t be, because history’s verdict is clear. In olden times, European monasteries owned vast, self-sufficient agricultural estates. From the start, those situated in southern climes grew grapes and made wine, while further north, barley and other cereal grains were fermented into beer.

In neither instance did varying depictions of “sin” enter into this estimably practical equation. Wine and beer efficiently preserved the value of perishable foodstuffs, provided a finished beverage that could be sold or bartered, and offered daily caloric nourishment to the monks. So it goes today, albeit on a vastly reduced scale, given that monastic estates were confiscated and dispersed during the Napoleonic era.

More recently, certification as a Trappist brewery (an accredited appellation of origin) proceeds according to three basic tenets: Brewing must take place on the grounds of the monastery; monks must retain involvement and control of the brewing operation, although secular brewers and helpers can be hired; and finally, a portion of the profits accrued from brewing must be donated to specified charitable purposes.

In this era of short-lived consumable objectification, it’s easy to forget about the monks themselves, flesh and blood inhabitants of places built, maintained and organized for the purpose of religious devotion. As opposed to my own personal belief system, beer is only a small component of a typical monk’s existence. During the course of lives spent exploring the relationship between man and God, these pious figures earnestly follow the time-honored Rules of St. Benedict and the guidelines of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance.

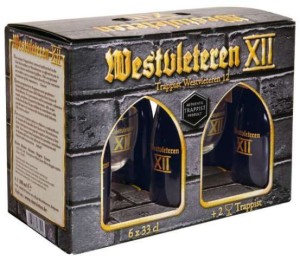

Concurrently, you can bet your last flagon of Dark Lord that earlier in the week, when lathered and trembling beer enthusiasts queued outside selected package stores to lay claim to their rightful Westvleteren XII gift packs, these Rules of St. Benedict were on the minds of very few.

However, in a spirit of ecumenical thoughtfulness, I chose to avoid the crowds, sip session ale, and sift through the monks’ own venerable playbook in search of clues to answer the question asked by a good friend:

I got my Westvleteren, so now what?

Begin by watching your mouth. Chapter 6 of St. Benedict’s little red book suggests that monks practice moderation in speech, although not maintain complete silence. They may say what is necessary in the course of daily life, but not engage in idle conversation.

This goes for you, too. Now that you possess six bottles of Westvleteren, reticence is helpful, lest previously unknown Facebook “friends” suddenly materialize at your doorstep, supplicating like a dervish near the shrubbery.

Accordingly, Chapter 7 considers the necessity of humility, and given the rarity of your newfound beery treasure, refraining from boastfulness is a fine way to preclude acts of spiteful vengefulness on the part of those who’ll not be receiving an e-vitation to next weekend’s tonsured Trappist theme party and poker night.

Chapter 42 urges monks to make room for edifying nighttime reading and silent, thoughtful contemplation before their bedtime. Before removing the caps from your grail, learn more about Trappist beer in general and Westvleteren in particular. Open a classic guidebook by Michael “Beer Hunter” Jackson. Think about places, people and how they fit.

Most importantly, resist the temptation to insult God by logging into Ebay.

If you cannot avoid lusting in your heart at the prospect of the riches to be gained by sating the greed of your fellow Westvleteren-less beer geek, then Chapter 5 further reminds us that we must display “unhesitating obedience” to what is lawful, as judged by the monastery’s Father Superior. Permission is duly granted to consider me your solemn, fatherly figure: Go and drink your Westvleteren, share it with others who are less fortunate, or even resell it for cost if absolutely necessary, but if you’re caught profitably trading on the black market, there will be certain repercussions.

Some of these penalties are outlined in Chapters 23 through 29, which note a graduated scale of punishment for “contumacy, disobedience, pride, and other grave faults.” Shouldn’t drinking warm Bud Light Lime through a soda straw await on-line bootleggers?

Or worse?

Perhaps Chapter 3 addresses this point, because it stipulates a calling of all monks to council to address matters of importance in the community. Be careful, of you just may be sentenced to Milwaukee’s Best, instead.

But seriously … yes, I’m fortunate to have consumed Westvleteren on several occasions from the Café de Vrede, located across the road from the abbey of St. Sixtus, and it is mighty fine ale, indeed. Your money was well spent, and with it, renovations can be made at the abbey.

Should your Westvleteren be aged? Maybe, maybe not. If you’re the disciplined sort, hide two of the bottles and come back to them in a year, but probably no longer than that.

The most interesting and educational use for a bottle of your newfound Westvleteren might be a three-way pairing with its fellow Trappist, the marvelous Rochefort 10, and St. Bernardus Abt. Both of these like-minded libations are freely available hereabouts, and at reasonable prices.

To my palate, Rochefort 10 and Westvleteren are neck and neck as “best of Trappists,” while St. Bernardus is the secular ale perhaps closest to them, having been licensed for many decades by the abbey before all brewing was taken back behind the walls.

Finally, remember a rule not included in St. Benedict’s book: Think globally, drink locally. Don’t treat your Westvleteren like an investment. Enjoy it with a friend or two, at your table, with some stinky cheese and crusty bread. Ponder the meaning of life. Savor Westvleteren precisely because it makes you happy.

Go forth, and proceed.